- Home

- Nayanika Mahtani

Across the Line Page 2

Across the Line Read online

Page 2

‘There. That’s our stone tower. Do you remember how to play pithoo, Loki?’

Tarlok nodded vigorously, ‘We have to break the stone tower with the ball.’

‘Yes, but you only win if you can then rebuild it without getting hit by the ball.’

‘But don’t we need more people to play, Toshi di?’

‘Tsk, in my version we can play with just the two of us. Do you want to play or not? Once Biji comes back, that’s the end of our pithoo.’

Toshi quickly glanced over her shoulder to check if her mother was on her way back from the market. Both she and Tarlok knew that as soon as she was home, they would have to go indoors and have their customary bath before dinner.

‘Let’s start quickly then, Toshi di,’ said Tarlok, hopping from foot to foot to warm up.

Toshi shut her left eye and aimed the ball at the pile of stones. She hit her target dead on, causing the stone tower to topple over. She whooped with joy. Tarlok ran after the ball. He scooped it up and threw it at his sister. The ball hit Toshi squarely in the back just as she was picking up the stones to rebuild the tower.

‘I got you!’ said Tarlok, grinning.

‘Ha! You’re cheating. It’s just that you can pick up the ball faster because you have three thumbs. If you had two, like the rest of us, then we’d see who wins.’ Toshi crossed her arms, tucking her hands under her armpits, as she usually did when things didn’t go her way.

‘That doesn’t make any sense. I’m just better,’ said Tarlok, delighted to see his sister getting riled.

‘We need a referee. I’ll bring Nanhi out so she can be our referee.’

‘Huh? Nanhi’s a doll! How can a doll be a referee?’

‘Of course, she can. She speaks to me. I’ll be back in a second.’

Tarlok slammed his palm against his forehead in despair at his sister’s strange convictions. Toshi ran into the house to get her favourite rag doll, one that her mother had sewn for her on her fifth birthday. While he waited, Tarlok picked up the green pebble from the ground—casually tossing it high in the air and deftly catching it.

As Toshi climbed the staircase to her bedroom, she could hear the distant sound of raucous chanting. It wasn’t like anything she had heard before. It seemed to be drawing closer by the minute—so much so that Toshi could feel tremors in the ground that rattled the shutters of her bedroom window.

Entering her bedroom, Toshi quickly picked up her doll and peered out of her window to see what the ruckus was about. She saw a frenzied mob approaching, brandishing long sticks as they surged forward. Now they were just a few houses away. Her gaze moved closer home. And Toshi’s heart stopped.

Tarlok was nowhere to be seen.

The doll fell from her nerveless fingers on to the street below. Within minutes, Nanhi was trampled upon, mangled by the mob. Toshi watched in shock as her precious rag doll lay there torn apart, in two exquisite halves, connected by a thousand threads.

Brushing away her tears, Toshi tore down the stairs to look for her brother. Just as she was about to leave the house, her father entered and quickly bolted the door.

‘Papaji—Tarlok! He’s outside. We need to get him!’

‘He isn’t outside, Toshi. Your mother must have . . . She must have taken him to Yasmin’s house upon seeing the rioters,’ said Baldev. His breath was rapid, he looked deeply disturbed. ‘Go to the terrace with Badi Ma and Bade Papa—I will bring Tarlok and your mother and join you.’

Toshi began to protest, but just then, her grandmother Chand emerged from the kitchen, halfway through her cooking, ladle in hand. Her grandfather Lekhraj, who was in the midst of lighting the evening diya in their prayer room, also entered the hallway, still holding the lit match.

‘What is going on? Who are these people, beta?’ Chand asked.

‘They’re from the neighbouring village, Biji,’ said Baldev, hastily shutting the windows one by one. ‘The borders have been announced. Rawalpindi is now in Pakistan.’

The ladle dropped from Chand’s hand. ‘What! But . . . but how can that be?’

‘No. No, there must be some mistake,’ muttered Lekhraj, almost to himself. The flame from the matchstick scorched his finger, but he barely noticed.

Baldev blew out the match and took his parents gently by their hands, herding them and Toshi up the stairs, as fast as he could manage.

‘It’s better if you all wait on the terrace. Hindu homes are being targeted.’

‘But the rice is half-cooked—it’s still on the flame,’ protested Chand.

‘I’ll turn the gas off, Biji. You all wait upstairs please until this mob passes.’

Chand held Toshi close as they walked up the stairs, wrapping her dupatta protectively around her, as if it were a shield that would keep the mob at bay. Baldev grasped his father’s arm, as he hobbled up the railing-less staircase.

‘Wait here. I’ll be back soon,’ said Baldev, leaving them at the terrace landing.

As he turned to go, Baldev noticed their elderly neighbour, Zulaikha Gafoor, standing on her terrace, leaning over the edge of the parapet, looking down. Her face was ashen—as if she’d seen a ghost. Baldev followed her gaze. The angry band of marauders, armed with sickles, axes, sticks and spears, had stopped right outside Baldev’s house. Their leader was barking incendiary orders.

‘Flush out each and every kaafir! Don’t spare a single one of these infidels.’

Zulaikha gestured urgently to Baldev to bring his family on to her terrace. ‘Quickly, Baldev beta. All of you hide here. They will kill you,’ she whispered hoarsely.

Zulaikha’s frail frame was now the sturdiest support the Sahni family had. Baldev took one look at the barbaric frenzy of the rioters. He picked up Toshi in his arms and took a leap across the gap that separated the two terrace walls. Then he returned and helped his elderly parents make the difficult crossing, while Zulaikha extended her hand to help from the other side, each fervently hoping that they wouldn’t be spotted by the mob below.

‘I’ll be back with Nalini and Tarlok,’ Baldev whispered to them, as they sat crouched on the terrace. He took his parents’ and daughter’s hands in his and touched them to his eyes.

‘Wait until these rioters leave, beta,’ urged Lekhraj.

‘It’s not safe to go . . . ’ protested Chand.

‘Papaji! Someone’s entering our house—through the kitchen door!’ gasped Toshi. Peeping through the diamond-shaped holes in the parapet, she had noticed a man in the gloaming, sideling towards the rear entrance of their house.

Baldev cautiously raised his head over the edge of the parapet and saw him too. On looking closer, he realized that the man was his childhood friend, Abrar Ansari. Baldev felt a knot tighten in his stomach, as he watched Abrar quietly inch closer. Why was Abrar risking his life, approaching their house at this time? Abrar was almost at their kitchen door when someone from the mob noticed the tulsi plant in the Sahni family’s courtyard—a dead giveaway of a Hindu abode.

‘Look, a kaafir!’ he shouted, spotting Abrar’s furtive movements.

The cry ricocheted off the walls, getting the mob’s attention, even amidst all the clamour.

‘What’s a kaafir, Badi Ma?’ Toshi whispered to her grandmother. Chand didn’t reply. With trembling hands, she pulled Toshi closer. From the road below, Toshi could hear Abrar’s pleas.

‘I’m not Hindu. I’m Muslim. Please, believe me!’

But the mob was in no mood to listen. The man who had spotted Abrar brought his axe down on Abrar’s skull. The crack resonated through the air. Abrar collapsed in a bloody heap, losing consciousness. One rioter doused him in kerosene while another set him ablaze.

‘Allahu Akbar!’ their cries rang out, triumphant.

Chand covered Toshi’s eyes with her palms, as they sat huddled on the floor. Toshi flinched at the icy touch of her grandmother’s usually warm hands. She wriggled free and peered through the holes in the parapet once again.

‘Abrar Chachu�

�s burning, Papaji!’ she screamed.

Instinctively, Chand clamped her palm over Toshi’s mouth, afraid that they would attract the attention of the rampaging mob. Numb with shock, Baldev watched his friend’s limp body burn. Still on his knees, he scrambled towards the edge of the terrace to go down to Abrar, but his mother clutched his arm.

‘Don’t go, beta—they will kill you too—’

She stopped mid-sentence because their collective attention was diverted by the overpowering smell of smoke and the roar of shattering window panes. They watched in disbelief as their house succumbed to the inferno that engulfed it. The fire hungrily devoured everything in its path. Toshi couldn’t tear her eyes away from the wisps of red and blue flames that were licking at the familiar walls of what was once her home.

Toshi’s head throbbed. Biji and Tarlok. She wanted her mother and brother. Safe from the fire and the mob. By her side. That was all Toshi could think of.

The rioters were beginning to move on, in search of their next target. Baldev was already at the far edge of Zulaikha’s terrace, making his way back downstairs.

‘Meet us in the attic when you return, Baldev beta,’ called Zulaikha, wrapping her arms protectively around Toshi and Chand’s shoulders as, still crouching, they inched towards her terrace door.

Baldev turned to look back.

‘Thank you, Zulaikha Baaji.’

‘You call me your elder sister, yet you thank me,’ she chided, her voice thick with emotion. ‘Go now, get them quickly!’

Toshi watched her father cross over to what was left of their terrace. She heard the familiar creak of the jaali terrace door as it opened. She watched him hurry down the first flight of stairs.

It was the last time ten-year-old Toshi ever saw her father.

Musaafir Khaana

17 August 1947

New Delhi, India

‘Musaafir Khaana’ was what their house was called. A rest house for travellers.

The name was misleading, giving the impression of a wayside inn. Rather, this was more in the way of a grand haveli, even if it was in need of some upkeep. A semicircular driveway lined by amaltas trees led to the wide verandas flanking the front door. Black, wrought-iron balustrades secured balconies that overlooked the overgrown gardens.

In the living room, Arjumand Haider was completing the embroidery on a new set of towels for her guest bathroom. Her extended family was due to come down for Eid, and she wanted everything to be shipshape and ready for them.

Her son, Javed, seemed restless—more so than usual, today.

‘There’s been more trouble, Ammi. Even in Aligarh. Bhaijaan also thinks it’s better for us to leave. Apparently, Junaid Khan—that news reporter for the Dawn—has been hacked to death. Bhaijaan says Muslim families everywhere are being targeted and butchered. Even the children aren’t spared.’

His mother looked up from her embroidery and shook her head. ‘Javed, these are all just the vile schemes of people who want to disrupt our country’s unity. It will pass. Did you not hear about how the Mahatma was cheered when he visited Lucknow?’

Javed sighed. ‘I don’t know what to believe any more, Ammi. Your sister and family are talking of leaving for Karachi. Now Bhaijaan also wants to go. And Rukhsana is due to have the baby next month. I’d rather our baby is born in—’

His mother looked up sharply. ‘Say it!’ she snapped, ‘You’d rather that the baby is born far away from the place where generations of our family have lived and died. I don’t know what this world is coming to, Javed. Do what you want. I will die here and be buried next to my husband.’ She stabbed at her embroidery angrily.

Just then, their elderly cook, Ghanshyam came running into the house. ‘Bibiji! A mob of rioters is approaching our streets. It is not safe for you here any more. You should leave immediately. They say the rioters are headed towards Azad Nagar. Please come with me. My home is humble, Bibiji, but you can hide there safely until you get a chance to leave.’

Arjumand looked up from her embroidery, ready to launch into another tirade, but something in Ghanshyam’s eyes told her that this was not the time. She shifted her gaze to Javed, whose forehead was lined with worry.

‘Ghanshyam is right, Ammi,’ he said, coming to her side. ‘We need to leave. Immediately. Rukhsana!’ His decibel level rose with the tide of his panic, ‘Where is she?’

‘It’s Sunday. She’s at the orphanage, as usual,’ his mother replied.

‘I’ll go and get her. Ammi—please pack your things. We’ll leave as soon as I bring Rukhsana home.’ Javed rushed out of the house.

Arjumand gathered up her embroidery and walked to her room in a troubled reverie. The events of the past few months seemed absolutely senseless to her. It was as if the whole world had lost its mind. She opened her cupboard and gazed at the vast array of saris and shawls hanging there. Row upon row of silks—Kanchipurams and Banarasis, chiffons and handwoven cottons, not to mention the exquisite pashmina and shahtoosh. In a corner of the cupboard, wrapped in muslin, lay her emerald green wedding gharara, its beautiful silver zari as resplendent as it was on the day she had been wed.

Her eyes fell on her dresser, with the many photographs of her family arranged on it. Her husband as a little boy, standing with his parents, against the imposing backdrop of Musaafir Khaana. Arjumand herself, in her bridal finery with her handsome husband. The two of them dressed in Kashmiri phirans on their honeymoon in Gulmarg, chaperoned by a clutch of aunts as was the tradition, all dutifully smiling for the camera. Her parents with five-year-old Javed and all his cousins on their first-ever horse ride on the ridge in Simla. Sepia memories of little moments that had defined her world.

Arjumand sat down heavily on the edge of her bed. What could she leave behind? What could she possibly take?

An hour later, Arjumand had only managed to pack her prayer mat, the photographs on her dresser and a few clothes, when there was a knock on her bedroom door. Arjumand turned to see Ghanshyam hesitating at the threshold of her room.

‘Yes, Ghanshyam? Has Javed sent you to call me?’

‘No, Bibiji. I just came to say that Raghu is downstairs.’

‘Oh! I haven’t met him in so long. He has forgotten us now that he has got a big government job, huh?’

Raghu was Ghanshyam’s son, whom Arjumand had known since he was a little boy. It was upon Arjumand’s insistence that Raghu had been sent to school rather than be groomed to follow in his father’s footsteps as domestic help. When Raghu completed his schooling, Arjumand had used her contacts to get him a compounder’s job in a government hospital nearby.

Ghanshyam shifted awkwardly from one foot to the other, grappling for the right words, ‘He’s here to say that you should take refuge in the hospital for the night, Bibiji,’ he said apologetically. ‘He doesn’t think our home is safe enough for you. He’s got a taxi waiting for you outside.’

Arjumand clicked her tongue in exasperation. ‘All this is not necessary, Ghanshyam. All of you are overreacting—let me speak with Javed and sort things out.’

‘Javed Sahib is already at the hospital with Rukhsana Bibi, awaiting your arrival, Bibiji. Raghu spotted them near the orphanage and took them to the hospital, as the insurgents had already started making trouble. Then he came here to get you and . . . ’

Ghanshyam’s words evaporated as he heard distant chants of ‘Har har Mahadev! Har har Mahadev!’ His face grew pale and his voice took on a desperate urgency, ‘Please, Bibiji. We need to be quick. Please go with Raghu. These rioters are opportunists—ransacking homes and . . . committing terrible atrocities . . . please leave, Bibiji—’

He broke off, too upset to talk. Arjumand shut her eyes and sighed heavily. ‘If you say so, Ghanshyam. But I will return soon—as soon as this dark cloud lifts.’

Ghanshyam’s eyes glazed over, ‘I’ll be waiting for that day, Bibiji.’

Arjumand reached into her cupboard and handed Ghanshyam an embroidered silk purse. ‘In case I miss Rag

hu’s wedding at the end of this month, give these ruby earrings to his wife from me. You’ve done more for us than family would, Ghanshyam.’

Ghanshyam quietly wiped away a tear with his sleeve. He had worked with the Haiders his whole life, just as his father had before him. Seven decades of loyalty stood steadfast. ‘This . . . your having to leave like this . . . I’m so . . . so sorry, Bibiji.’

He shook his head, unable to find the words to express his deep sense of shame at what his community was inflicting upon the Haiders.

‘It isn’t anyone’s fault, Ghanshyam. It’s a madness that has possessed us all,’ said Arjumand. ‘Now take me away from here, before I change my mind. And make sure we are ready with the Eid preparations when I return. The whole family will descend on us in three weeks.’

As if Nothing Had Happened

18 August 1947

Rawalpindi, Pakistan

The platform was stained crimson; strewn with bloodied bodies. People heedlessly stepped over the corpses as if they were fallen leaves, whilst they madly scrambled to wangle their way on to a train. Pushing and shoving to get a foothold—anywhere. On the roof. On a window ledge. Or on the footboard, hanging precariously by the door handles of the carriages. Just as long as they were aboard a train bound for the India that lay across the line.

It was on one such train that Toshi and her grandparents were being urged to get on to by their neighbours, Zulaikha and her son, Khalid.

‘Once you’re across the border, you’ll be safe, Chachajaan,’ said Khalid to Lekhraj. ‘Please don’t worry, I will look out for Baldev, Nalini and Tarlok and put them on the next train as soon as I can. Things are so bad here—these people will kill you if you stay.’

Lekhraj looked at Khalid with vacant eyes. ‘How do you kill someone who has died already?’ he asked flatly.

Khalid swallowed hard. Fighting back her tears, Zulaikha turned to Chand, ‘Do it for Toshi—please!’ she said, clutching Chand’s hands. ‘They won’t spare her life here.’

Toshi stood by Chand’s side, transfixed by what she saw around her. The ten-year-old’s porous gaze soaked up everything around her, especially things that adult eyes chose not to see. Like the train that had arrived a few moments earlier from India, with blood seeping out from under the carriage doors. Toshi watched wide-eyed as railway officials flung the piles of lifeless bodies that lay inside the coaches on to the platform, as casually as one might flick a piece of lint off one’s coat. She felt threads of nausea rise up in her throat.

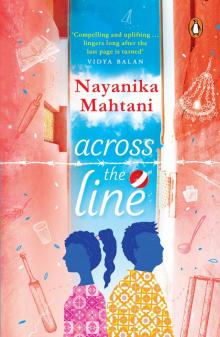

Across the Line

Across the Line